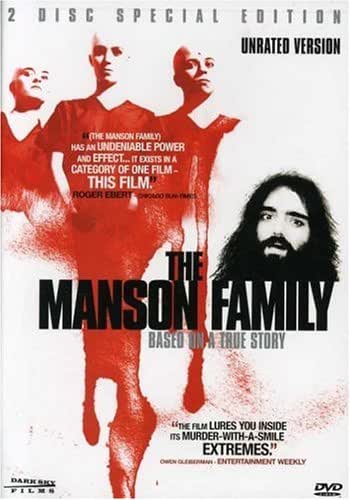

THE MANSON FAMILY

***½/**** Image A Sound A+ Extras A+

starring Marcello Games, Marc Pitman, Leslie Orr, Maureen Alisse

written and directed by Jim VanBebber

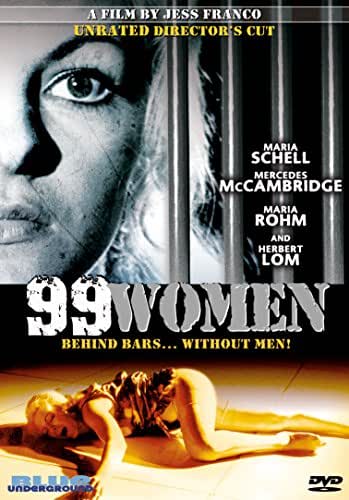

Der heiße Tod

**½/**** Image A Sound B Extras B

starring Maria Schell, Mercedes McCambridge, Maria Rohm, Rosalda Neri

screenplay by Peter Welbeck

directed by Jess Franco

by Walter Chaw Attempting exactly the same thing as Mel Gibson's bloodier and no less exploitive telling of a hippie religious leader whose teachings produced immediately sanguine results (with Gibson's martyr going on to establish what is possibly the bloodiest nation in the history of the planet), Jim VanBebber's laudably disquieting The Manson Family is distinguished by its self-awareness as a document of hate rather than one of hosanna on high. Fifteen years in the making, it demonstrates a commensurate level of passion in its creation, the same obsession with recreating the period in the mode of its predominant artform (static representation for the one, drive-in cinema for the other), culminating in an orgy of violence that's gotten a bad rap precisely because there's no prurient thrill to be gained from it. Close examination reveals, in fact, that the deeds of Manson's merry men and women aren't shown in as much detail as they could have been–the chief excision being the fate of Sharon Tate and her in utero baby. The madness of King VanBebber, then, seems to have a method: not to, like Gibson's blood-soaked reverie, revel in every minute detail of flayed viscera and spilled humours, but to recreate the uncomfortable viciousness of loose ideology set free in the schizophrenic fin de siècle sandwiched between free love and its Vietnam War bloodletting counterweight. The Manson Family is about how tragic is the loss of mind and life; The Passion of the Christ is about how tragic it is, for their sake, that the Jews and the Romans didn't know what a bad motherfucker they were messing with. Context is everything.

|

It's the summer of love, man, and Charles Manson (Marcelo Games) has gathered a small group of college graduates and upper-class silver spoon babies to live on the ranch of a blind man, where they can philosophize to their heart's content in the Carlos Castaneda school of stupid hallucinations. When Charlie fails to score a recording contract for his bad folk music (shades of Castro not winning a minor league pitching invitation with the Yankees), he urges his ideological kinder to go on "creeps" in the houses of the wealthy, rearranging their furniture and committing petty larcenies while the keepers at the gate slumber. One night, however, Charlie, with a head full of The Beatles' psychedelia, allegedly spurs his "family" to start a race war by murdering some of the hoi polloi and splashing racially-charged epithets on the walls in virgin blood.

The Manson Family is fun in a grindhouse kind of way for exactly five minutes–that's all the time it takes for the tits and giggles to turn sour on the tongue. Shot as a faux-documentary focusing on the family, it melds "footage" from 1969 with present-day interviews in which the aged and supposedly wiser cultists appear confused about what exactly happened back in sunny old California that was "groovy" enough to unearth, for a while, the contents of their Jungian basements. Dr. Timothy Leary's invitation to turn on, tune in, and drop out never came laced with more barbed spines than when a fireside bacchanal turns into a dog's-blood drinking contest, complete with hallucinations of Charlie-as-Christ sprouting horns as he's tossed onto the pyre. VanBebber's freak flag flies proudest, though, in the moments between the freak-outs, as a particular, pungent variety of drunken puerile enthusiasm (the type that leads to mob violence, fraternities, and Focus on the Family) seeps off the screen and into our memories of our lowest, most frightened moments. It's the scene in Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind where our hero is forced to remember the time he was forced to participate in the desecration of an animal's corpse extended to feature-length–the tongue probing the exposed nerve that leads directly to the knowledge of ourselves at our ugliest and most naked. Our association with these people is a quesy thing: not only are we not surprised that the seasons in the sun morph into a couple of nights of abattoir indulgence, we're also hostage participants. The Manson Family isn't a perfect film by a long shot (framing stories are the pits), but it portrays atrocity as atrocity with the mean precision of John McNaughton's Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer. You feel sick and indicted by it–and that's exactly how you ought to feel.

From an exploitation film set in 1969 to one released in 1969, Jess Franco's 99 Women (more accurately, "Woman 99") is probably the best example of the Women In Prison exploitation genre–which, frankly, never quite caught my attention in the same way that the "Ilsa, She-Devil of the SS" series or the Naughty Nuns did. What this says about me as the pitcher or catcher in domination scenarios is, admittedly, too much, but regardless, I came to this sub-genre late enough to not be terribly titillated by the Sapphic exploits of our European beauties, if interested in a detached way in smut peddlers and connoisseurs. Consider the case of Jess Franco, a soft-porn merchant extraordinaire who never met a rack-focus or zoom shot he didn't love. (The better to avoid costly camera/lighting set-ups and having to change locations, of course.) What better milieu for Paul Williams's creepier cousin, the fever king of trash cinema, than the close, monochrome cinderblock environs of a female prison? The result is a picture that's surprisingly restrained in regards to gratuitous cheesecake (shower scenes are more effective in men-behind-bars films, anyway) and which actually tries to address issues like prison violence, corrupt administrations, and a flawed legal system. It's The Shawshank Redemption in nearly every way that matters except that its ending has more integrity than that of its cozy big-budget brother–something that shouldn't come as much of a surprise, except that it does.

The innocent looking for justice is Maria Rohm and the prison investigator trying to clean up a system that's bigger than her is Maria Schell (sister of Maximilian). Along the way, there are The Color Purple moments of sexual tenderness and self-discovery, some medium-unpleasant rape intrigues, and a few camp-heavy monologues that Franco punctuates with his trademark cheesiness. The evil warden is played by the voice of the demon from The Exorcist, Mercedes McCambridge, in an implicit homage to Hume Cronyn's evil warden from Jules Dassin's homoerotic classic, the 1947 incarceration melodrama Brute Force. She's paired with the great Herbert Lom as twin tormentors of their burlap-clad charges on an island prison called the "Castle of Death," which shares the island–to the misfortune of the naughty ladies–with an all-male mirror-prison on the other side. While the potential carnage in the setting is squandered (a giant snake is also woefully abused), what works just fine are a few flashbacks that function as the girls' sob stories. The best is a hallucinogenic striptease (by "veteran con" Rosalba Neri) before a high society crowd that plays like how a lot of Eyes Wide Shut probably should have played: erotic, charged with class schisms and the toll of exploitation on all women, even those in the audience. The undercurrent of chagrin in a few of the young ladies in the crowd is captured with a pole-axing amount of skill by Franco–possibly the only time in the director's career (save a few similar moments in Venus in Furs) that he treats women as complex–and sympathetic–human beings.

THE DVDs

MPI and Blue Underground, respectively, shepherd The Manson Family and 99 Women to DVD in commensurately magnificent presentations that should bring a glint to the eye of the fanatic. The Manson Family's fullscreen transfer is utterly faithful to VanBebber's intention of recreating a period exploitation mien (compare his "lush" moments with Franco's cinematographic strategy for 99 Women to see how well he's done)–"utterly faithful" meaning in this instance that the print is scratched (sometimes by hand), and that it's grainy and jittery as though the sprockets on the actual reels were compromised. VanBebber's strategy of fabricating a new antique is in line with Guy Maddin's stated attempt to do the same–the distinction being that The Manson Family actually resembles what people were watching in Texas drive-ins circa the 1970s whereas Maddin's films look like the state in which modern viewers can see silent and early sound pictures. One strikes me as valid, the other strikes me as arch, almost smug. Meanwhile, I felt a time or two as though subliminal suggestions were being rocketed into my prefrontals with The Manson Family's DD 5.1 soundmix, whose atmospherics are fulsome and dynamic. Of all the things lost in the modern conversation, the primary casualty of the current genre crop is the use of sound to ratchet up the tension. Watched sans picture, the film still has the chops to raise the goose pimples, though it's worth mentioning that the alternate DD 2.0 stereo option doesn't cut it in the same way. Two trailers for The Manson Family plus an extensive photo gallery close out disc one.

The second platter of this two-disc set houses a trio of lengthy documentaries. Let's start with "In the Belly of the Beast" (73 mins.), a document of Montreal's Fant-Asia film festival from 1997 that follows fringe filmmakers as they shop their genre wares in front of a live audience. Transgressive, femi-revenge, ultra-violent, extremely low-budget products arrive seeking distribution or at least fruitful discourse. What I love is how well this little documentary captures every festival environment through this tiny festival's environment. It replicates in an extraordinarily genuine way how filmmakers at almost every level of success discuss film as well as of how festivalgoers are just the distillation/magnification of Joe Everybody's militaristic politicism, nascent anti-intellectualism, and general ignorance. Listen to the endless line of drool leaking from the hole of a self-described French-Canadian "Mother and feminist activist!" off camera; to the equivocal defensiveness of filmmaker/festival coordinator Karim Hussain, who pre-emptively attacks critics of his film for not appreciating his anti-narrative magnum opus; to Peter Rist, the cinema studies professor from Concordia University, who says that he hates a revenge film for the same reasons he dislikes America, i.e., the eye-for-an-eye mentality that he sees as something like a social disease. Pretentious, insane, deluded–the festival experience is concentrated asshole-ism that is sometimes revelatory (as it was when I watched Cronenberg's Spider sitting next to Gaspar Noé at Telluride) but is more often the absolute pits. "In the Belly of the Beast" is a remarkable insight into why film criticism is possibly the most depressing non-dental profession in the universe.

I love, too, that Nacho Cerda is interviewed at length. The director of the astonishing, gruelling necrophilia opus Aftermath, Cerda is something like a genius whose gift for cinematic narrative is, unfortunately, tied to subject matter far too gruesome for the average moviegoer. That said, if you've seen Aftermath, you're changed: it takes you to a place as a human animal, all meat and sex, that's astonishingly unsettling. Watch it in a gruelling double bill with Claire Denis's revelatory Trouble Every Day and shudder at the insectile emptiness at the core of the animal self. Complaining that the flick is impenetrable, Chas Balun, editor of DEEP RED magazine, confronts Cerda post-screening in a way that is familiar, uncomfortable, and predictably non-productive. (The fuddy-duddy critic masking his fuddy-duddiness behind his search for meaning vs. the frustrated filmmaker wondering how meaning could have been missed, not realizing that his success at unsettling people is itself already sublimity.) But what's more unsettling than the film (essentially an autopsy and a corpse rape)–and herein lies explanation in part for the title of the piece–is the post-screening Q&A, in which self-righteous clowns ask Cerda vaguely moralistic questions about a picture they've flocked to in part because it was double-billed with Cannibal Ferox. The same snotty fest attitude that renders something like Rabbit-Proof Fence critic-proof there, too, is alive and well and living in every single exclusive arts event in the world.

Produced by Blue Underground, "The VanBebber Family" (76 mins.) is an excellent, deeply reflective making-of featuring talking-heads with cast and crew that find VanBebber in a contemplative mood, making it clear that there's nothing prurient about his picture–that, in essence, the label of "exploitation" in relation to this picture refers more to "medium" than to category. The mantra of "pain is temporary, film is forever" is the kind of thing that reminds guys like me why we sit through stuff like xXx: State of the Union, Monster-in-Law, even Star Wars: Episode III–films that the filmmakers themselves wouldn't see and have as much as said they don't give a shit about beyond the bottom line. The Manson Family, for everything that it is and isn't, is a labour of love–and at the end of it the day, it's deeply respectful of film: its power, its elasticity, and its eternity. (Maybe the reason George Lucas is constantly tampering with his movies has something to do with an urge to tamper with historical evidence.) Finally, ten minutes with Charles Manson himself in a reel cobbled together from archival interviews reveal the guy to be as nutty as an Almond Rocha. They also reminds us just how good is that Charles Manson-as-Lassie sketch from "The Ben Stiller Show."

The unrated director's cut of 99 Women debuts on the format in a simply beautiful 1.78:1 anamorphic widescreen transfer. While Franco never met a Vaseline-smeared lens he didn't abuse, the folks at Blue Underground transform his romance-novel hackery into something that feels extraordinarily textured and undeniably filmic. I've never seen a Franco film look better than a cheap Italian cannibal flick prior to this incarnation of 99 Women, and though the accompanying 2.0 Dolby mono soundtrack is occasionally tinny, it's not so in any way that doesn't imply fidelity to the source. Special features include, in addition to a short, 19-minute interview wherein a chain-smokin' Jesus ("Jess' Women") recalls Fritz Lang's appreciation for his erotica, a trio of "Deleted & Alternate" scenes in lousy condition. An extended version of Maria Rohm's rape flashback (5 mins.) suggests a primary inspiration for the gang rape in Kubrick's A Clockwork Orange, while the second elision (16 mins.) offers an alternate version of Zoie's flashback replacing the kinky striptease with something that involved neither Franco nor Neri. Sourced from a Greek videotape, it's all shots of seagulls, empty swings, and hollow melodrama. (In other words, sort of hilarious, but mostly boring.) The third and shortest trim (2 mins.) is an extended ending that betrays the picture's laudable darkness. A nicely-remastered theatrical trailer, an extensive, five-part stills gallery, and a DVD-ROM feature housing an indispensable .pdf file on Franco written by VIDEO WATCHDOG's Tim Lucas, round out the DVD. Originally published: April 25, 2005.

![The Fox and the Hound (1981) [25th Anniversary] + The Little Mermaid (1989) [Platinum Edition] - DVDs|The Fox and the Hound/The Fox and the Hound II (2006) [2 Movie Collection] - Blu-ray Disc littlemermaid](https://i0.wp.com/filmfreakcentral.net/wp-content/uploads/2011/08/littlemermaid.jpg?resize=150%2C150&ssl=1)