**/**** Image B+ Sound A- Extras A-

starring Ben Cross, Ned Beatty, William Russ, Jill Carroll

written by Philip Yordan and Fernando Fonseca

directed by Camilo Vila

by Bryant Frazer The Unholy, a moderately-budgeted religious horror drama from Vestron Pictures, is notable mostly for its outsized ambitions. Sure, it has the B-movie elements you’d expect from a late-1980s genre outing with Satanic undertones. There’s a troubled, tempted priest, a couple of gory set-pieces, and a phalanx of latex monsters that storm into the final act. But it also boasts moody cinematography, leisurely plot development, and a mini-dream team of character actors. Want to see Ned Beatty and Hal Holbrook play a scene together for the only time in their careers? You want to see The Unholy. How about an elderly Trevor Howard, in his final role, as a blind demonologist? The Unholy is the movie for you. Or the recently-deceased Ben Cross as a Catholic priest with an expiration date of Easter Sunday? You guessed it: The Unholy. It’s an unusually earnest variant on those Catholic-themed horror movies that became A Thing in the 1970s, after The Exorcist and The Omen established an audience for lurid horror dressed up with religious themes and prestige names.

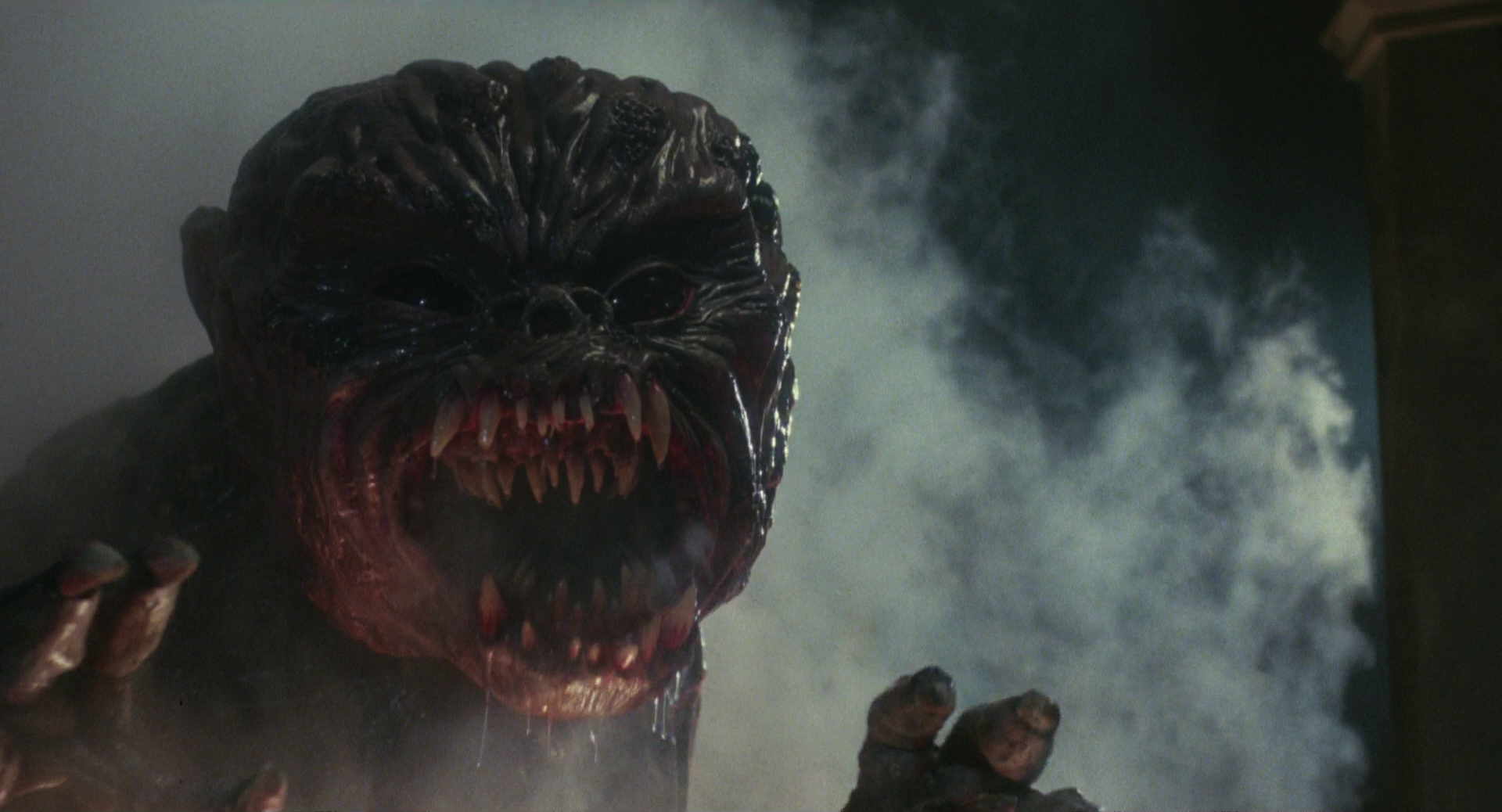

It’s easy to see why Archbishop Mosely (Holbrook) and Father Silva (Howard) believe Father Michael (Cross) is the chosen one who can defeat the demons haunting St. Agnes Church: it takes a lot to make him lose his cool. Cross’s performance is a veritable barometer for how seriously we are to take The Unholy‘s shenanigans from scene to scene. After he miraculously survives an attempt on his life, Michael is clearly baffled by the turn of events, but to call him “freaked out” would be exaggerating. His reaction to other bizarre events is similarly stoic. He’s only vaguely perturbed after an anonymous dying man gasps at him, “You’re in danger, John Michael,” and he barely bats an eye when police Lieutenant Stern (Beatty) reveals to him that the last two priests who ran this church were both murdered on Holy Saturday. He reacts a little more strongly when he wakes up in the middle of the night with a crotch full of snakes and then answers a phone call from Hell. It’s a relief when a knockabout troupe of ridiculous rubber monsters shows up at the end of the film to give him the opportunity, finally, to kick ass for the Lord.

The Unholy has its moments, but tonally it’s confused. The presentation is surprisingly leisurely and low-key except in those parts where, boy howdy, it suddenly isn’t. The very first scene features a flamboyant redhead (Nicole Fortier) in a sheer purple dress (and nothing else) seducing a priest, then ripping out his throat like a werewolf of London. The enormous crucified Jesus hanging behind the altar seems horrified by the spectacle, but a hooded angel statue with a boyish visage and a Mona Lisa smile that I can only describe as Evil Harry Potter looks on approvingly. An opening like that? Let’s say it sets up sex-and-horror expectations The Unholy is ill-equipped to meet. As it turns out, director Camilo Vila thought he was making one kind of movie–a supernatural whodunit unified by themes of faith and temptation–but the studio decided it wanted a full-on horror flick complete with jump-scares, gratuitous gore, and a ridiculously uncoordinated four-legged Final Demon (it’s not just a guy in a suit; it’s two guys in a suit!). I’m not sure those impulses are inherently incompatible, but they sure don’t mesh here. Given what we see in the prologue, why would anyone watching think that sexually abused waif Millie (Jill Carroll), occult nightclub impresario Luke (William Russ, wielding an outrageous but authentic New Orleans accent), or even the housekeeper Teresa (Claudio Robinson) would be skulking around killing priests? THE NEW YORK TIMES, whose reviewer wondered whether Millie, rather than Father Michael, was the demon’s real target, was as puzzled as anybody.

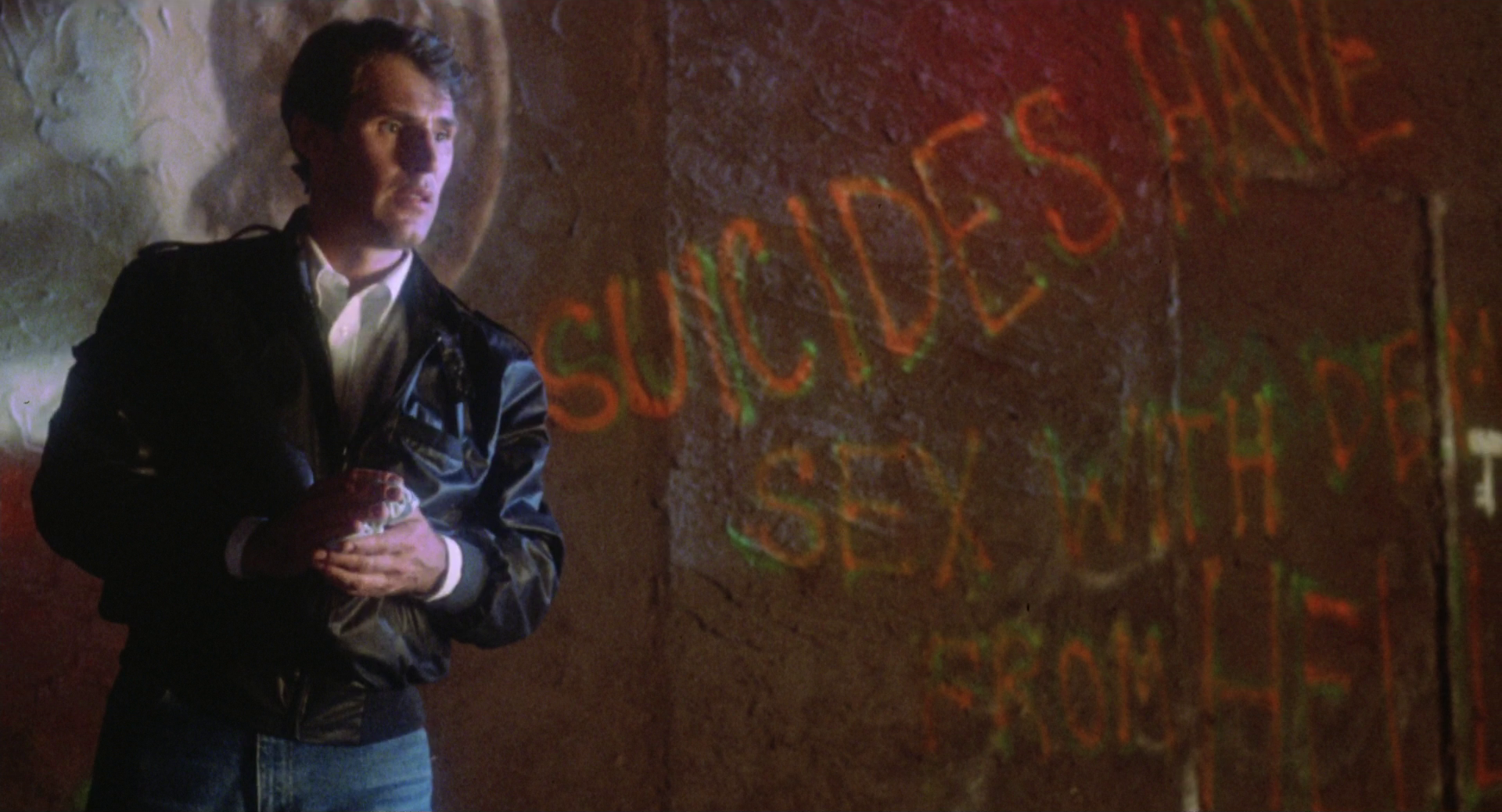

You get some idea of the movie The Unholy wants to be in an early scene with a man standing on a ledge outside his hotel room, 17 stories up, threatening suicide. Father Michael has been summoned to the room by the police because the man on the ledge has asked for him by name. When Michael shows up, he immediately establishes his credentials as The Cool Priest, lighting a smoke and low-key chatting with the would-be jumper like he’s barely bothered by the prospect of a suicide. Leaning outside and attempting to coax Claude back over to the windowsill “so I can see your face when we talk,” he looks down from the dizzying perch and promises, “It’s just as high from here.” The colours, the lighting, and the camera angles are all very well-considered, and Cross’s performance is intriguingly cryptic. He doesn’t smile, or suggest that Claude has a lot to live for, or any of that crap; indeed, as he wraps the rosary around his fingers, he gives the wall a good hard stare that says he’s seen some things. Cross makes it hard to tell what Father Michael is really thinking and, for a good portion of the film’s running time, he makes the question genuinely interesting.

But then the film loses patience with itself and cuts to a jump-scare squeezed out of the footage discarded when Vila was fired from the project and the whole thing was recut against his wishes. That’s just one in an ongoing series of clunky flash-cuts with aspirations to shock value that are deployed again and again by editor Mark Melnick (Remo Williams: The Adventure Begins) as the film progresses. They all have the whiff of desperation about them. There are also odd bits of business throughout, like the club chick who pours herself a Coke, only to leave the scene immediately without drinking any of it, that may indicate where major surgery occurred. It’s hard to tell whether Vila’s director’s cut, incorporating a very different climax with effects work supervised by an uncredited John Dykstra (!), would be much better on the whole. At least it might have some thematic integrity. What we have instead is not just dull but a mess as well, even by gonzo horror standards.

Despite my complaints about the movie itself, I have to admit that The Unholy‘s BD release is quite impressive. The new master seems to have come not from the camera negative, but maybe from a first-generation interpositive. While both positive and negative density dirt are occasionally visible, this is mostly a very clean transfer, correctly letterboxed to 1.85:1, with appropriate levels of relatively crisp film grain. (Some darker shots are a tad murkier.) Colour rendition is quite strong, with vivid reds, blues, and purples emerging forcefully from rich shadows. Blacks do occasionally appear crushed, though film grain is still visible in the toe of the image, indicating that any fault is with the source material rather than a failure to resolve shadow detail in the digital transfer. On the other hand, I thought the whites were a little hot in some places, but there’s still a nice roll-off in the highlights, thanks in part to DP Henry Vargas’s use of diffusion. The 2.0 audio track is robust and distortion-free, unfolding nicely to a matrixed Dolby Stereo surround mix. Both dialogue and music–the Roger Bellon score is rich with synth, percussion, and vocal choir–are clear and undistorted, and any noise has been attenuated without creating distracting artifacts.

Director Camilo Vila comes out swinging on his audio commentary, declaring that “the movie was, in my humble opinion, destroyed” by studio interference. Nathaniel Thompson from Mondo Digital conducts an excellent feature-length interview with Vila, who details the origins of the project (a script dating to the early 1970s), his own aspirations for it, and what was made of it when the studio handed it over to Melnick, whom he calls “an editor who wanted to direct.” Interestingly, he claims he didn’t think much of the climax he shot, complaining only that the “corny” reshoots didn’t improve on the original. He has exceptionally kind words for Cross and Howard and claims that casting director Carol Dudley was his strongest ally among his production colleagues. “Carol saw the same movie I saw,” he says. “We wanted to do an A movie, not a horror movie.”

Two more audio interviews are offered, both dealing with the film’s musical score. Composer Roger Bellon, whose largely electronic music replaced an orchestral score by Fernando Fanseco, is interviewed by Michael Felsher for about 41 minutes, and the rest of the feature-length track is filled with his synth-heavy, percussive instrumentals. Bellon discusses his background as a composer, including the introduction of electronic music to the industry in the mid-1980s, before moving on to his work on The Unholy specifically. Assigned to replace Fanseco on the project with a deadline less than two weeks away, he ended up holing up at an L.A. studio and improvising a score. Next up is Fanseco himself, who is additionally credited, improbably enough, as the film’s production designer and co-screenwriter. Fanseco remembers that Vila had already been fired before he arrived in L.A. to compose his very traditional score–he cites Bernard Herrmann and Max Steiner as influences–and says the producers eventually replaced him because they wanted a more contemporary sound. Fanseco talks for about 15 minutes, then we hear just under 40 minutes of music from his discarded score. Conducted by none other than Bellon, it’s brassy and bombastic, with plenty of Herrmann-derived ostinatos, an even broader array of percussion sounds, and angelic/satanic choral swells that put the capital C on the film’s Catholic themes and give the whole affair a more prestigious veneer.

Fanseco returns for the first of three interview featurettes, “Prayer Offerings: with Production Designer & Co-Writer Fernado Fonseca” (19 mins.), in which he freely admits to getting swamped by his multiple roles on the film: “I was wearing too many hats.” He says he was invited to become the production designer when he started to sketch out a plan for how a specific scene could be executed and the producers offered him the job. He refers to his and Vila’s preferred “emotional” tone for the movie, which he reiterates was meant to be a murder mystery, and laments the studio’s re-edit. “It did not encourage me to work on any other film projects,” he says.

Also in over his head was make-up effects designer Jerry Macaluso, who was hired to work on the film straight out of high school and spent much of his time sculpting maquettes on the coffee table at his parents’ house. In “Demons in the Flesh: The Monsters of ‘The Unholy‘” (22 mins.), he describes the production as an oddly serene, no-adult-supervision experience where his team learned as they went along, throwing around piles of the production’s money to solve problems and fix screw-ups. “Nobody ever came and checked on us,” Macaluso says. “John Dykstra said to me, towards the end, ‘Do you know you’ve spent almost $300,000 and we don’t have a creature?’ I was like, ‘Sorry. I mean, we’re trying.'” Special effects artists Steve Hardie and Neil Gorton show up near the end of the piece, but only Macaluso, forever regretful that he botched his opportunity to be the next Rob Bottin, brings the pathos. It wasn’t until he saw the finished movie that he realized nearly all of his creature work had been replaced. It’s a genuinely amazing story that might even make for a better movie than The Unholy.

Next up is “Sins of the Father: with Ben Cross” (19 mins.), and, unlike some well-known actors who seem to pretend that their doorbell is busted and their phone number has been changed when Blu-ray producers try to reach them for comment on their appearances in schlocky 1980s horror outings, Cross sits for the interview and discusses The Unholy almost as if it were Chariots of Fire–an acting job no less worthy of his effort than any other. He makes note of his own Catholic upbringing and says the original script reminded him of a Hammer Horror film, but also reveals that he was offered the role in part because he was Vila’s roommate and Dudley was a “close mutual friend.” He has stories about Ned Beatty and Trevor Howard and William Russ, whom he calls “the Method actor of us all.” Endearingly, he has plenty of time for Nicole Fortier, who he calls out for her courage on set. “I haven’t seen many films where you’ve seen a male actor full-frontal,” he says. “I’ve seen many bare-chested actors and we’ve seen many bare-breasted actresses, but we’ve also, in the last 10 years, seen full-frontal nudity [from women]. Well, come on, guys. What’s your problem?”

The big prize for the movie’s fans is its original ending, included as a continuous 15-minute sequence closing the film. The quality is good, considering this is an outtake–the transfer is much darker and dupier than that of The Unholy itself, but it’s easy enough to see what was captured on film. The audio track, complete with Fanseco’s discarded score, hasn’t had much clean-up done to it but it, too, sounds better than you’d expect. As far as the actual content goes, I definitely prefer this ending for less-is-more reasons. I can see why studio executives might have found the demonic creature here to be underwhelming, yet it’s certainly no dorkier than what they ended up with in the finished picture.

I will say that I am a fan of the storyboards created by Diane Reynolds-Nash for the film’s revised climax. The ideas–images of virgin sacrifices, genital mutilation, make-out sessions gone horribly wrong, and other gory tableaux worthy of a Herschell Gordon Lewis project–don’t work very well in the movie proper, but they’re pleasantly bizarre in this isolated presentation, where they constitute a real curio, like a cross between a Japanese horror manga and the cover of “In the Court of the Crimson King”. They’re on board as a bizarre video slideshow (19 mins.) set to Roger Bellon’s score.

The exhaustive (and, frankly, exhausting) package also contains a slideshow of production stills (12 mins.), including lobby cards, international release posters (the Italian one is groovy!), and the type of gore shots that would have been submitted to FANGORIA magazine. A standard-def collection of TV spots (2:15) features a hilarious post-screening audience reaction compilation where one teenager gushes, “Ben Cross is great, really fantastic!” and another declares, “First there was Aliens, then Aliens 2, now there’s The Unholy!” The two one-minute radio spots (“More controversial than The Exorcist, more terrifying than The Omen“) are fine but just don’t have the same camp value. An adequate but unremarkable theatrical trailer (1:17) closes out this admirable installment in the Vestron Video Collector’s Series.

102 minutes; R; 1.85:1 (1080p/MPEG-4); English 2.0 DTS-HD MA (matrixed surround); English subtitles; BD-50; Region A; Lionsgate