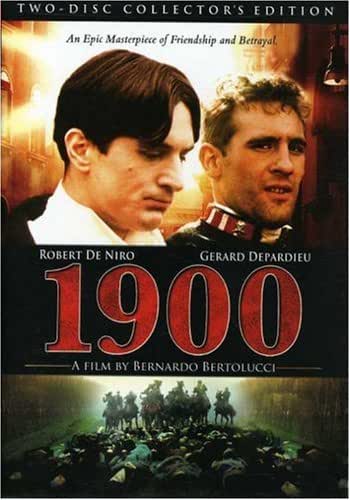

1900

**½/**** Image A- Sound B+ Extras B+

starring Robert De Niro, Gerard Depardieu, Dominique Sanda, Francesca Bertini

screenplay by Franco Arcalli, Giuseppe Bertolucci, Bernardo Bertolucci

directed by Bernardo Bertolucci

LA COMMUNE (PARIS, 1871)

****/**** Image B- Sound C+ Extras C+

directed by Peter Watkins

by Travis Mackenzie Hoover In this corner, Bernardo Bertolucci, weighing in with a massive budget courtesy of Alberto Grimaldi and a cast that includes De Niro, Depardieu, Sutherland, Lancaster, Hayden, and Sanda. Over here we have Peter Watkins, working for peanuts on a single soundstage with a cast of nobodies recruited from Paris and its environs. The fight, as it turns out, is more than one over who can make the longest movie (5hrs15mins for Bertolucci, 5hrs45mins for Watkins) or grab the most attention. The issue is: what are the conditions necessary for a revolutionary epic–moreover, what conditions get in the way? This is the real purpose of comparing 1900 and La Commune (Paris, 1871) (hereafter La Commune), for each film throws down for the Communist cause but only one is conscious of the nuances. Where Watkins and his troupe constantly reframe the idea of what it means to foment revolution, Bertolucci thinks he's got the idea–and proves, through mindless repetition, that he really doesn't.

|

THE UNIVERSAL CLOCK (2001) |

|

|

| Debuting in 2001 and now supplementing La Commune (Paris, 1871) on First Run's R1 DVD release, The Universal Clock: The Resistance of Peter Watkins (76 mins.) is an NFB documentary on the making of the film. Here, Peter Watkins's methods take a backseat to interviews with such participants as a social worker who believes the social system is designed to keep the ruling elite in power; a mother who is amazed at Watkins's inclusion of her "fatso" self; and an Algerian whose papers have been confiscated. Underlining the liberating nature of the production, these talking-heads are contrasted with footage of the Cannes television festival, at which various sinister individuals from the Discovery Channel and the like explain the dumbing-down and standardization of information that Watkins lives to counter.

This would be fine were it not for the Canadian-ness of the whole enterprise: director Geoff Bowie can't resist the urge to pontificate over the nature of the footage like a bush league Chris Marker, and he winds up gilding the lily: the interviewees (friend and foe) would have pretty much made the case for Watkins's brand of filmmaking without Bowie's monotonous voiceover. Further, one walks away from the film feeling desolate as opposed to invigorated: unlike La Commune itself, The Universal Clock lacks faith in its audience and winds up spelling doom and gloom. The "universal clock," by the way, is TV nomenclature for the medium's tendency to regulate the length of documentaries so that they fit into predetermined time slots, regardless of the organic length for the subject at hand. Alas, Bowie's film seems like it might already qualify.–TMH |

While the pictures themselves are separated by 24 years, there are enough points of contact for the comparison to stick. Both directors come out of the turmoil and experimentation of the '60s–the last time in history you could genuinely express revolutionary sentiments and not be written off as a crackpot or a bore. And both are trying–desperately and on a grand scale–to hone their unfashionable sentiments into something relevant to a period (the mid-'70s for Bertolucci, the Aughts for Watkins) that may not want to hear them. The difference, however, lies in that Watkins was never trying to create a name for himself as an artist the way Bertolucci was: the Italian was a megalomaniacal little fucker commanding the wind and the earth in as ostentatious a manner as possible, whereas Watkins was trying to give the common populace a voice. Despite the similar mission statements of the two films, you walk away from one with more of a choice than you do from the other.

Let's get down to specifics. 1900 starts off with the surefire attention-getter of a partisan being shot by a fascist on liberation day, then segues into a bunch of peasant women goring a couple of unidentified fascists (Donald Sutherland's Attila and Laura Betti's Regina). One is overwhelmed by sensual things, specifically brutal violence, cheap irony, and Vittorio Storaro's indelible sun-dappled cinematography. We know that the victims of the peasantry can't be nice people (they're dressed in grey, after all) but not what they represent, yet the emotional pull is such that we're coerced into thrilling to their fate. By contrast, La Commune begins with a couple of actors (whose names I've tried in vain to track down) announcing that they are performers in the amateur recreation we're about to see. There aren't any emotional arrows telling us how to feel–it's a bald statement that announces the artificiality of the whole affair. An important distinction, as we shall see.

1900 subsequently jumps back in time to the day of Verdi's death and the birth of two children from opposite sides of the tracks. "Old Patron" Burt Lancaster is ecstatic at the arrival of grandson Alfredo (to be played by Robert De Niro), while the birth of a peasant bastard named Olmo (later Gerard Depardieu) merits somewhat less enthusiasm. Lancaster hands out wine to his workers on the occasion, meriting the incredulity of grey peasant eminence Leo (Sterling Hayden), who expresses the sentiment that nobody on his side of the line would ever receive this kind of sendoff. Still, the idea sort of hangs in space, as everything the patrone owns–which is practically everything in the movie–is shot in such a way as to emphasize its immense cost. The period detail is rendered so exactingly that it draws attention to itself and its beauty (infernal Storaro again). The thin, limply-drawn Marxist point–that the rich get rich and the poor get screwed–is ultimately overwhelmed by the commodity value of the whole enterprise.

La Commune, by contrast, is uninterested in niceties to the extent that it calls attention to its own artifice. The opening has announced the film as a construct, and we're quickly introduced to the conceit (that Paris has official and Commune TV stations in 1871) that will further destroy the idea of total illusion. In its place, Watkins attempts to place us within the context of the Paris Commune, partly through intertitles that feed us the details of Napoleon III's Prussian war disaster and the chaos that threatened to turn into revolution by giving rise to the poor-and-working-class resistance. We are intimately introduced to the intolerable conditions that spiralled out of control and forced a response–and the actors, who have been researching their own largely-improvised roles, impassionedly fill in the gaps. One doesn't notice property, one notices human beings.

Bertolucci, for his part, never wavers from his ultra-simplistic thesis. Alfredo and Olmo are used quite schematically to illustrate the distance between the rich and the poor: though the two remain friends (for all intents and purposes) for the bulk of the movie, their drifting is used as a measure of how capitalism is–or ought to be–doomed. The younger incarnations are happy to taunt girls with frogs or compare genitalia, but as adults, Alfredo is enamoured of his possessions and power to the point where he ceases to have the will to fight his father's gravitation towards the nascent fascist movement. As Olmi becomes more communist, Alfredo stops doing anything substantial to help challenges to his authority. (Once again, rich=bad, poor=good.) This does nothing to distract from the fact that the director has managed to become his own patrone, ruling resources and bankable talent for the greater glory of Paramount Pictures.

We could chalk this up to obliviousness if not for Bertolucci tipping his hand when he introduces the character of Attila. Played with relish by Donald Sutherland, the character is not allowed to simply be a fascist–which, in the universe of any serious leftist, is damnation enough. No, in Attila's first substantial scene, he kills a cat by ramming it with his head. Later, as though that weren't ample evidence of his villainy, he and his slavering girlfriend Regina (Laura Betti) molest a little boy at Alfredo's wedding before smashing the child's head open to prevent him from tattling. It's here that the film goes from crude to insulting: we're apparently so stupid that we can't be counted on to hate fascism for fascism's sake. For all of Bertolucci's pro-peasant rhetoric, he's hard-pressed to provide a real sense of how peasants, communist or otherwise, are suffering under fascist rule. Pretty, rhetorical words do not translate into vivid description of living conditions.

After setting the scene, Watkins plunges us into a vivid re-enactment of every stretch of the Commune and its rise and fall–not through the material comforts of set design but through the sentiments of Paris citizens as expressed to, ahem, "Commune TV." Of course there was no TV at the time of the commune–the idea is to create a means by which the well-informed cast can express the desires of those manning the ramparts. Moreover, Watkins has no control over how these are expressed: it's up to the actors to show the solidarity of and/or fissures in the opinions behind the barricades, and to offer reasons for their views. We're less confronted with one man's bullying us into sympathy than we are dropped into conditions that encourage us to listen and decide for ourselves.

It's soon obvious that La Commune is less about 1871 than it is about now. It takes that one brief shining moment and holds it up as a test case for revolutionary community and organization, as leftists have often done in the 130-odd years since. The masterstroke comes when, sometime in hour four, Watkins lets the actors break character and discuss their own beliefs–all the while maintaining the fictive space of the Commune and commingling the documentary with the re-enactment. And they keep relating the historical events back to the present, reminding us that despite the comforts of the first world, things are nearly as bad as, or worse than, they were in 1871. (As an intertitle points out, the world's richest/poorest nations' ratio of wealth has gone from 7:1 to 72:1.) By the end of the movie, the "real" actor-speak is indistinguishable from the characters–and the gauntlet has been thrown down to learn from the experience exactly how, or if, we can change.

Compared to this, Bertolucci's approach to leftism is pathetic sloganeering. Somewhere along the line, he got the idea that Marxism is neat, and while he's willing to let his enthusiasm spill over into every extroverted frame of his film, he's completely defeated when it comes to suggesting praxis. This is epitomized by the penultimate scene of 1900, wherein the peasants and partisans who have just routed the fascists start waving a giant patchwork of stitched-together communist flags around a courtyard. One doesn't get the sense of people living with the idea of leftism or trying to go through the motions of building a communist society–it's merely a red-coloured photo op. La Commune is all about the implementation of its ideas; and as the commune goes into decline and experiences schisms and confusions, it reveals the need for commitment beyond throwing a party and hoping everybody shows up.

Bertolucci and Watkins are equally ambitious, but their ambitions are completely different. 1900 aims to change the world but instead flatters and manipulates the audience: its melodramatic excesses banish every thought from your head, beating you down with entertaining but deadening blood and thunder. It's the type of "ambitious" movie you put with subsequent '70s kingmaker movies like Apocalypse Now, New York, New York, and Heaven's Gate: the ambition is to move mountains, command crews, and dominate the frame with expensive hardware and production design. Meanwhile Watkins, for a paltry 300,000 francs, liberates your consciousness from the orders of most movies and asks only that you question the images that bombard us from every angle. His allegiance to the audience is an act of self-deference almost without precedent in the whole of narrative cinema. The resulting power shift from filmmaker to audience is nothing less than shattering.

I confess I have a soft spot for 1900: not only is it a memory from my high school days (and my late, lamented hometown rep house), but it's also a big crazy thing you can't help but smirk at for its sensual derangement and ludicrosity. Alas, I saw it prior to La Commune, which wiped the smirk off my face. Watkins's epic makes even the best political films seem hopelessly inadequate, the work of artists with agendas they want to foist upon you rather than of artists leading you to your own conclusions. Every filmmaker, film student, and film critic should watch the astounding, magnificent La Commune and ponder the consequences of aesthetics that defeat personal agency in the name of doing good.

Spreading the film across two platters, Paramount's Two-Disc Collector's Edition DVD release of 1900 does the movie reasonably proud: any problems with the exquisitely-saturated 1.78:1 anamorphic widescreen transfer, such as a high (if fluctuating) volume of grain, are endemic to the source print. In the long run, it's worthy of Storaro's name. Although the accompanying Dolby 2.0 Surround sound isn't terribly animated, the sometimes-terrible dubbing resonates with lamentable clarity. Extras begin with the second disc's "1900: The Story, the Cast" (14 mins.), in which Bertolucci discusses his distaste for the mass-market "monoculture" that was homogenizing Italian culture, his film's reminder of the country life from which the nation sprang, and his casting of the then-ascendant pair of De Niro and Depardieu. Meanwhile, "1900: Creating an Epic" (14 mins.) ropes in Storaro with Bertolucci to elaborate on many of their artistic decisions with regards to the film: the (trite) seasonal metaphor; the motives behind specific uses of light; and the Chinese-style trial of the patrone at the end of the film. These interview clips alternate interesting insights and simplistic explanations.

La Commune (Paris, 1871) looks a little more ragged as presented on DVD by First Run Features. The 1.66:1 non-anamorphic widescreen transfer was clearly sourced from a PAL master of Betacam SP elements, hence combing and ghosting artifacts; the b&w image is a tad grainy besides. Granted, the lo-fi nature of the video and the attendant Dolby 2.0 mono audio is artistically defensible. In lieu of La Commune's longer broadcast version (which runs some 9hrs25mins), First Run presents The Universal Clock (see sidebar); a Watkins filmography, a DVD-ROM teacher's guide, and trailers for The Take, War Photographer, The Internationale, and 49 Up round out the 3-disc set. The whole shebang is packaged in a double-width keepcase with a swingtray insert.

- 1900

315 minutes; R; 1.78:1 (16×9-enhanced); English Dolby Surround, French DD 2.0 (Mono), Italian DD 2.0 (Mono); CC; English subtitles; 2 DVD-9s; Region One; Paramount - La Commune (Paris, 1871)

345 minutes; NR; 1.66:1; French DD 2.0 (Mono); English subtitles (non-optional); 3 DVD-9s; Region One; First Run

![Peanuts: Deluxe Holiday Collection [Ultimate Collector's Edition] - Blu-ray Disc 126827830_80_80-2871638](https://filmfreakcentral.net/wp-content/uploads/2012/11/126827830_80_80-2871638.jpg)