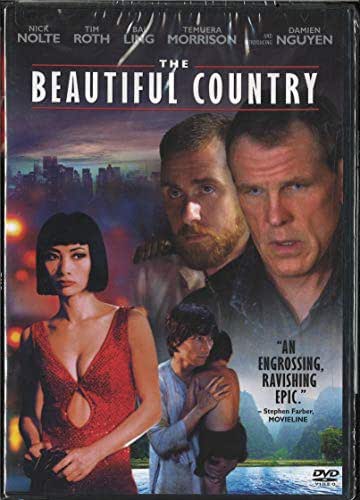

THE BEAUTIFUL COUNTRY

**½/**** Image A Sound A Extras B-

starring Nick Nolte, Tim Roth, Bai Ling, Temeura Morisson

screenplay by Sabina Murray

directed by Hans Petter Moland

ME AND YOU AND EVERYONE WE KNOW

*½/****

starring John Hawkes, Miranda July, Miles Thompson, Brandon Ratcliff

written and directed by Miranda July

Shijie

****/****

starring Zhao Tao, Chen Taisheng, Jing Jue, Jiang Zhong-wei

written and directed by Jia Zhang-ke

by Walter Chaw Norwegian director Hans Petter Moland makes films about isolated individuals trapped in simulacra of motion, and his best work is savage and melancholic: a trip taken by broken people to the bedside of a dying mother in Aberdeen; a pilgrimage made by a poet to locate his masculinity in the company of a maniac in Zero Kelvin. Even his first film, the quiet Secondløitnanten, touches on men oppressed by the caprice of nature–of other men driven to their natural state and the situations that melt away the lies that keep our lives liveable. Moland's films are beautifully framed (picaresque, it's not too much to say), capturing in their sprawling, austere landscapes the plight of individuals dwarfed by the mad, engulfing entropy of existence. He's a good fit with American auteur Terrence Malick, in other words–so it's without much surprise that Malick approached Moland to direct The Beautiful Country, a project he'd worked on, on and off, for a period of years before deciding that the producer's role would better suit him in this instance. The result is a picture that looks, sounds, often feels like a Malick film–even more so, it goes without saying, than Moland's early output does, leaving the project something that feels uncomfortably like ventriloquism. And though I'm a fan of both puppet and master, I find that I prefer the one drawing a line to the other rather than pulled around by the master's strings.

|

That's neither here nor there for the bulk of The Beautiful Country as we follow Binh (Damien Nguyen), the product of a tryst between his mother and an occupying Yankee soldier (Nick Nolte) during the Vietnam police action and an outcast due to his half-caste status. "Lower than dust" is what his foster family calls him–thus he goes on a quest to find his mother in Hanoi, a new life in Manhattan, and his father in Texas. Because this is precisely the kind of film that it is, he's saddled with an adorable younger half-brother, Tam (Tran Dang Quoc Thinh), on the lam when a comedy of misunderstandings results in tragedy and flight from his long-lost mother's side. More, a whore with a heart of gold (Bai Ling), a corrupt smuggler captain (Tim Roth), and the captain's corrupt lieutenant (Temeura Morisson) light the way of his journey. Of course someone will turn out to be blind, his external affliction reflecting his internal torment (and greasing the wheels for a none-too-subtle stab at the arbitrariness of racism), and someone else will be dead, fed to the grist of screenwriter Sabina Murray's clumsy, ham-handed finger-pecks that are at least a full measure gawkier than Binh's too-easy literal quest. (If locating a hayseed in a haystack were this easy, he could've called first.) But that's punching narrative holes in broad allegory–expecting a well-intentioned, high-minded, often too-obvious bit of social activism to resist swatting its flies with its rhetorical Cadillacs. I suspect Malick passed on this project without abandoning it because the script needed an overhaul, but for all the similarities to Malick, credit Moland–a brilliant director who doesn't need this coattail–for the few stunning images, the few thunderously understated moments, and the whispered, elliptical grace note that concludes the piece.

"Brilliant director" is also how flavour of the moment Miranda July is being hailed in certain Sundance circles for her directorial debut, the diary of self-love Me and You and Everyone We Know. The title refers to a page of dots and semi-colons and quotation marks (an invitation to consider gestalt if that's what gets you off faster) that young Peter (Miles Thompson) prints out for his little six-year-old brother Robby (Brandon Ratcliff)–encapsulating the picture's dual obsession with the cooling effect of technology on intimacy and the idea that post-modernism in the mouths of babes gains the heft of Delphic sibyls. Robby bumbles into a sex-chatroom and offers the proposition that he and his partner shit into one another's assholes into a Eurobosian eternity before agreeing to meet his partner (most probably a man, his brother assures) in a park. Delicate Peter, meanwhile, busts his cherry against the mouths of two competitive Lolitas, themselves preyed upon by a pedophile who posts vile suggestions for them on signs in his window.

But all's well in July's world as what can only climax in tragedy for these kids ends instead in poignant pretense while July sets her own character, daffy performance artist Christine, on the chase for Robby and Peter's befuddled shoe-salesman dad Richard (John Hawkes). Christine hangs socks off her ears, boils rabbits (just kidding), and follows Richard around until he agrees to give her a call at her cabbie business for people "too old to drive themselves." Sure, Richard will eventually ring because he feels just that way and, together, they'll find a home for a picture of a bird, jammed in the crook of a branch in the front yard. Contrived is not the point–too cute to follow through with its own bullshit is closer to the problem, as July is so infatuated by the sound of her own voice (indeed, Christine's performance art is over-dubbing still photos with psychodramas) that it drowns out the cries of her characters, who are well-sketched in moments but cut loose like a dinghy in the storm in most others. It's philosophy for arrested art and poetry students equipped with that "pathos-hued metaphor" switch that is the headwaters for bad folk music, bad poetry, and, verily, bad Sundance-approved motion pictures.

Issues of madness and love in a temporary and illusory universe are treated with more solemnity, beauty, grace–you name it–by Chinese master Jia Zhang-ke's haunted The World. Set in Beijing's World Park amusement centre (which recreates a hundred of the world's landmarks to scale in chintzy, amusement park-style), it spends time in a medium-shot remove with the park's performers as they clothe themselves in the emperor's new threads of assumed worldliness and borrowed weariness. "The Twin Towers were bombed on September 11th. But we still have them," says one park worker with pride to his visiting family, while another visitor remarks that the miniature Eiffel Tower looks just like the real one before confiding that she's never actually been to Paris. Most of Jia's speakers have never set foot on a plane, and when a wedding toast includes "world peace" and "women's rights," it speaks to a recognition of the greatest irony of globalization: that people who've never been anywhere, done anything, thought any grand design, are now pundits for profundity, philosophers of the new millennium with their wanderlust smothered in the cradle of un-acted-upon desires.

The World functions as a science-fiction of a place hermetically-sealed from the outside world with its inhabitants programmed into the contradictory existential response of knowing that they're in a bubble whilst believing that they're not. And, trickily, it functions as an allegory for our own conflicted place in modernity in the same breath. (Note a shot of a plane over a field of grey concrete columns as pithy, almost surreal representation of the frustrated Icarean ambition at the picture's heart.) Jia's first officially-sanctioned film after three unsanctioned ones (Xiao Wu (1997), Platform (2000), and Unknown Pleasures (2002)–masterpieces, all), The World is giddily anti-establishment and, moreover, recognizes hope as a thing with feathers roosting the hearts of his players, disenchanted with their stage and suspecting that outside the borders of their meticulously-structured fandango is just more of the same, but unmoored and drifting. Originally published: July 15, 2005.

THE DVD – THE BEAUTIFUL COUNTRY

by Bill Chambers Sony presents The Beautiful Country on DVD in a handsome 2.34:1 anamorphic widescreen transfer. The studio's 'scope titles are usually plagued by edge enhancement, but this one emerges from the telecine suite with nary a hint of it. There is, in fact, something coldly immaculate about the image; it inspires only a jaded shrug. Featuring crisp, audible dialogue and doing well by a relatively modest soundmix that places most of the ambience up front, the Dolby Digital 5.1 audio is equally adept. Extras include a feature-length commentary from director Hans Petter Moland and a 20-minute Q&A with screenwriter Sabina Murray. The former is very dry: Moland fixates on character motivation, which finds him taking the pretentious but no less easy route to narrating the movie. Aside from an interesting detour into his time in New York as a location scout for music-video pioneer Bob Giraldi, there's nothing here as penetrating as our own interview with the filmmaker. Meanwhile, the questions posed in the aforementioned featurette by a heard-but-not-seen interrogator grow so squirm-inducingly banal (e.g. "What is your favourite scene?") that the obviously-intelligent Murray starts to look like she's twirling on a spit. Although she's not, by her own admission, cinema-savvy, she manages to provide a great deal of insight into producer Terrence Malick's involvement (certainly more than Moland ever summons) and touches on challenges we may not have considered, such as the difficulty of writing broken English that doesn't sound condescending. Trailers for Saving Face, Heights, Oliver Twist, Saraband, Sueño, and Thumbsucker round out the disc, with the Saving Face preview cuing up on startup. Originally published: November 23, 2005.