***½/****

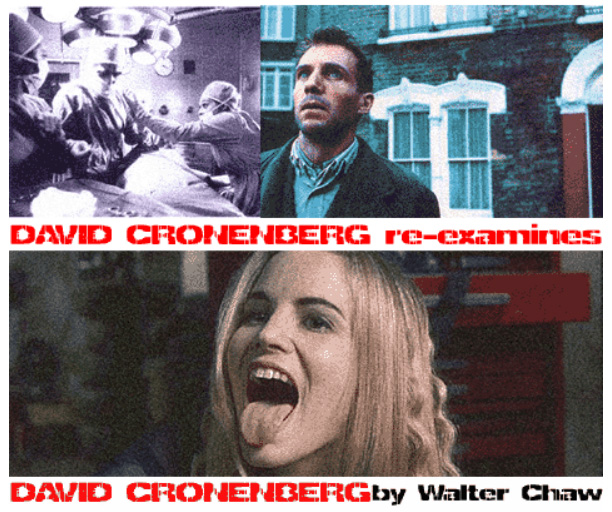

starring Ralph Fiennes, Miranda Richardson, Gabriel Byrne, Bradley Hall

screenplay by Patrick McGrath and David Cronenberg, based on the novel by Patrick McGrath

directed by David Cronenberg

by Travis Mackenzie Hoover After a period of indifferent projects, declining audiences, and three years of disconcerting silence, the unthinkable has become reality: David Cronenberg is back on top. His new film Spider intensifies all of his past thematic concerns with a pictorial eloquence practically unheard of in his oeuvre–it’s like watching one of the sex slugs from Shivers turn into a beautiful, fragile butterfly. For once, the trials of his sexually confused lead resonate beyond the merely theoretical, and for once, you feel his pain instead of contemplating it from a distance. The antiseptic restraint of Crash and Naked Lunch has been replaced with a dread and sadness that overwhelm you with their emotionalism; Spider is easily the best film he’s made since Dead Ringers, possibly even since Videodrome. I hope that it marks a turning point in the career of Canada’s most conspicuous auteur.

The opening is a quiet example of bravura filmmaking, with word and camera in perfect accord. A slow track down a train platform leaves us caught in a surge of disembarking travellers; by the time we reach Dennis Clegg (Ralph Fiennes), we see him as lost in the crowd, the bottom of the heap, and his affectations do nothing to dispel such a judgment. Wearing four shirts under his jacket and keeping a notebook in a sock, he is clearly mentally ill; as he wanders the streets of the nameless British city in which he’s arrived, we wonder if he’s a drifter without a home. But as Cronenberg follows him, trapping him in cruel perspectives and dwarfing him with the structure of a gas tank, we find his destination: a halfway house run by a robust lady (Lynn Redgrave) who leads him to the dingy room in which he is supposed to stay. Dennis continues to wander the streets, and we wonder again if we are simply to bear witness to the sadness of his travels and tics.

The film then shifts gear into a puzzle where Dennis is helpless in reliving his childhood. Specifically, he’s trying to piece together his parenthood, a mutable thing, as his memories suggest, with a father (Gabriel Byrne) who seems at first a good provider but soon appears to be a philandering cretin. As Dennis–“Spider” to his doting mum (Miranda Richardson)–watches like Johnny Smith in The Dead Zone, Dad approaches a snaggletoothed tart in a pub, and has it off with her under a bridge–but doesn’t she look a lot like mum? And is he watching his child self, or being his child self, or being his father in the alley? The Oedipal and psychosexual tension bubbles just beneath the surface as Dennis tries to pin down the good mother at the expense of her bad replacement. As he scribbles illegible script in his notebook and gazes guiltily at the gas tank, it is suggested that the key to his rage and confusion is based on a fallacy, that of removing the one side of the feminine from the other.

But that diagram is only support for the awfully melancholy temperament that Cronenberg and the screenwriter have concocted. It’s true that Dennis has a familiarly Cronenbergian need for control over the female, and that his attempts are predictably futile, but at last, he wants you to feel the agony of his defeat instead of noting it dispassionately. The director is more reliant on mood than the over-expository dialogue that often clogs his films, and he finds a sterling match in the sparse material by co-scriptor and source novelist Patrick McGrath, which offers few obvious cues to reason. Freed from the shackles of explanation, he evokes Dennis’s confusion through angular compositions that either trap him in their lines or thrust him uncomfortably forward. He makes us feel his guilt before we know why he feels it, complicating our feelings towards him before we can opt out of our identification. Spider is as harrowing for us as it is for its protagonist. We can’t walk away from his agony.

Debate will rage, as it usually does around Cronenberg, over the gender politics of the film, and as it walks the line between exposing misogyny and lamenting it, I can’t say all the news is good. But it’s still light-years ahead of his American competition–its Cannes snub baffles. You may not like where Spider ends up, but the journey, as it shows new dimensions to a man whose mind we thought we knew until he showed us how he felt about it, is so grippingly melancholy that you may not really care.